Learning Goals for this Unit

- to become familiar with vocabulary of invasive plants

- to learn what characteristics describes an invasive plant

- to become familiar with the distribution of invasive plants in Alaska

Definitions

1. Rights of way

Rights of way are corridors used for movement of people and goods, and placement of utilities. Rights of way may include:

- Roads

- Railroads

- Utility line easements

- Trails

Vegetation management in rights of way is essential for:

- Maintaining line of sight

- Safety

- Maintaining the structure of right-of-way

- Reducing damage to utility lines

2. Weedy definitions

Weeds are often spread on rights of way. To understand what we really mean by weeds we have to understand the difference between several terms used to describe these plants.

- Native or Indigenous plants are plants that live or grow naturally in a particular region without direct or indirect human actions.

- Non-native, exotic, alien, or non-indigenous plants are plants whose presence in a given area is due to accidental or intentional introduction by humans.

- Weeds are any plant, native or not, whose presence is undesirable to people in a particular time or place.

- Invasive plants, are non-indigenous plants that have the potential to establish and spread in natural areas, and agricultural properties where they cause harm to resources, the economy or the environment.

- Noxious weeds are plants that are regulated under legal statutes or regulations.

More on Noxious Weeds

Noxious weeds in Alaska are regulated in the “seed law” (11 AAC 34.020). This law contains prohibited and restricted noxious weeds.

The prohibited noxious weeds are not allowed for sale or transport in Alaska as the seed, or as a contaminant of anything that could successfully spread that seed.

Restricted noxious weeds are allowed for sale or transport, except that as a contaminant of seed restricted weeds have an allowable tolerance.

Take a moment to visit the Division of Agriculture website and become familiar with various noxious weeds.

Non-Native and Invasive Plants of Alaska

Information about non-native plants in Alaska can be found at the Alaska Exotic Plants Information Clearinghouse.

As you get introduced to invasive plant management and prevention you need to understand what an invasive plant really is and why it matters.

Not all introduced and spreading species become invasive

The difference between invasive, and a casually spreading non-native plant is often misunderstood. Very few species that are successfully introduced to a new area as an ornamental, agricultural, or conservation species (e.g. erosion control) ever become invasive. Approximately 10% of introduced species may casually spread, never actually causing problems. Of the 10% that spread only 10% may actually become invasive. This “Tens” rule is not steadfast, but the point is that very few introduced species ever become invasive.

Characteristics of a species that becomes invasive

Click each to expand for more information.

Escape from natural enemies

When a plant is introduced to a new area the fauna that kept the plant from growing uncontrollably in its place of origin are not present in the new environment. In some instances the native species adapt quickly to a non-native plant, and start to eat or otherwise use the plant in a way that keeps it under control. In other instances the non-native plant is not consumed or otherwise used, giving it a potential advantage over the native plants.

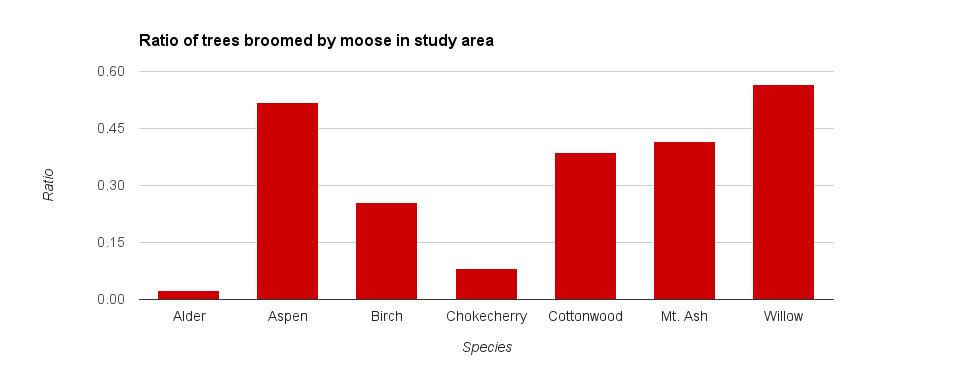

For example, the non-native chokecherry trees, European bird cherry and Canada red (Prunus padus and virginiana), are spreading throughout the forests in Anchorage, Fairbanks, and around other communities with planted trees. The plant is toxic to moose if too much is consumed. The lack of herbivore to consume the tree keeps it from experiencing the browsing pressure that results in a broomed architecture that other native tree species experience.

Multiple modes of reproduction

Plants reproduce by seed (sexually and/or asexually), and vegetatively with clones that arise from creeping roots (rhizomes), above ground runners (stolons), and/or stem fragments. Species like orange hawkweed are in part successful because they can reproduce by many of these methods.

Germinate prolifically

Some plants produce enormous amounts of seed, and may do so multiple times in the same growing season. High seed output makes for a seed bank in the soil that can overwhelm other species the next season.

|

|

Narrowleaf hawksbeard and hempnettle produce an abundance of seed, and can do so multiple times in the same season.

Able to disperse long distances

Whether by wind or barb stuck to an animal plants that can disperse for long distances spread rapidly.

High seed viability and persistence

Some plants produce seed that is highly viable, meaning nearly all their seeds produce new plants. When high seed viability is combined with dormancy that can last many years plants are able to germinate when the right conditions trigger the seed to sprout. These traits can make for a persistent population that lasts for many years even when actively controlled.

Physical traits

Tendrils for climbing and allelopathy are examples of physical traits that can give a plant an advantage over others. Tendrils are common on vines with a climbing and smothering growth habit. These plants can smother shorter plants, small shrubs, and tree saplings. Allelopathy is the use of chemicals that are released from roots or other parts of the plant that may prevent seedlings from growing or cause other changes in the soil that are not favorable to certain plants.

Which species take advantage of rights of way?

The ground within a right of way that plants can grow in is frequently disturbed through general use and maintenance activities. Plants that grow in a right of way are adapted to these frequent disturbances. Often these plants are the early colonizers after floods or fires. When a plant hitch-hikes on car tires, equipment, gravel, or in plant seed it can take root on the roadside. In some instances, we used to plant species because they were adapted to roadsides, and later we found out they are actually invasive. Some of the roadside invasive plants are problems for agriculture as they are adapted to the frequent disturbances associated with planting, harvesting, or grazing animals. Other roadside weeds are habitat generalists meaning they grow in a variety of different conditions. A habitat generalist may grow and spread along roadsides only to spread to wetlands or stream sides.

![Caption: Reed canarygrass is able to grow and spread along roadsides, but is highly adapted to wet soils. When roads intersect with wetlands, or rivers reed canarygrass can spread to these areas where it is considered problematic. [Image credit: National Parks Service]](https://weedcontrol.open.uaf.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2015/03/reedcanarygrass_5.jpg)

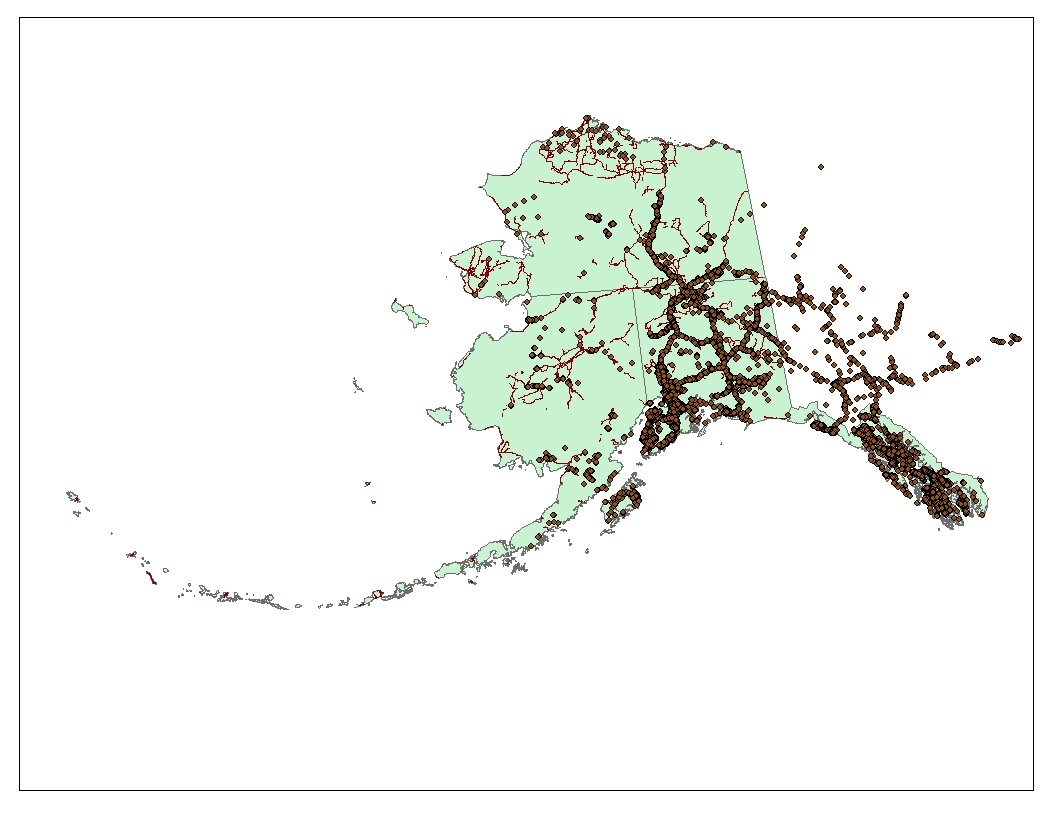

Distribution of invasive plants in Alaska and the relation to roads

We have already discussed that many invasive plants are highly adapted to roads, and this is evident from the distribution of invasive plants recorded in Alaska. Managers of invasive plants often begin survey of areas on roads, and check nearby public lands to determine if the plants have spread from the roadside. Managers survey this way because it is widely understood that roads are a corridor for weeds to move long distances to find suitable habitat that is adjacent to roads.